No edit summary |

m (→External links: add cat) |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 14 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Real-world}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

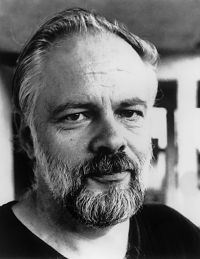

| + | [[Image:PhilipDick.jpg|frame]] |

||

| + | '''Philip Kindred Dick''' (b. December 16, 1928 Chicago, Illinois d. March 2, 1982, Santa Ana, California) , often known by his initials PKD, was an American science fiction writer and author of ''[[Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?]]'', the basis for the 1982 film ''[[Blade Runner]]''. |

||

| ⚫ | In addition to thirty-eight books currently in print, Dick produced a number of short stories and minor works which were published in pulp magazines. At least seven of his stories have been adapted into films. Though hailed during his lifetime by peers such as Stanisław Lem, Robert A. Heinlein and Robert Silverberg, Dick received little general recognition until after his death. |

||

| ⚫ | Foreshadowing the |

||

| ⚫ | Foreshadowing the cyberpunk sub-genre, Dick brought the anomic world of California to many of his works, drawing upon his own life experiences in novels like ''A Scanner Darkly''. His novels and stories frequently used plot devices such as alternate universes and simulacra, worlds inhabited by common working people, rather than galactic elites. "There are no heroics in Dick's books," Ursula K. LeGuin wrote, "but there are heroes. One is reminded of [Charles] Dickens: what counts is the honesty, constancy, kindness and patience of ordinary people." |

||

| ⚫ | His novel, '' |

||

| ⚫ | His acclaimed novel, ''The Man in the High Castle'', bridged the genres of alternate history and science fiction, resulting in a Hugo Award for Best Novel in 1963. Dick chose to write about the people he loved, placing them in fictional worlds where he questioned the reality of ideas and institutions. "In my writing I even question the universe; I wonder out loud if it is real, and I wonder out loud if all of us are real," Dick wrote. |

||

| ⚫ | Dick's stories often descend into seemingly surreal fantasies, with characters discovering that their everyday world is an illusion, emanating either from external entities or from the vicissitudes of an |

||

| ⚫ | Dick's stories often descend into seemingly surreal fantasies, with characters discovering that their everyday world is an illusion, emanating either from external entities or from the vicissitudes of an unreliable narrator. "All of his work starts with the basic assumption that there cannot be one, single, objective reality," Charles Platt writes. "Everything is a matter of perception. The ground is liable to shift under your feet. A protagonist may find himself living out another person's dream, or he may enter a drug-induced state that actually makes better sense than the real world, or he may cross into a different universe completely." These characteristic themes and the atmosphere of paranoia they generate are sometimes described as "Dickian" or "Phildickian." |

||

| − | These characteristic themes and the atmosphere of paranoia they generate are sometimes described as "Dickian" or "Phildickian." |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | ==Life== |

||

| − | ===Early life=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | Philip Kindred Dick and his [[twin]] sister, Jane Charlotte Dick, were born six weeks prematurely to Joseph Edgar and Dorothy Kindred Dick in Chicago, Illinois. According to various accounts, Dorothy was unable to properly feed and care for the newborns, and Jane was badly burned by an electric blanket. Dick's father, a fraud investigator for the [[United States Department of Agriculture]], had recently taken out life insurance policies, and an insurance nurse was dispatched to the home. Upon seeing the malnourished Philip and injured Jane, the nurse rushed the babies to the hospital, but baby Jane died on the way there, three weeks after her birth ([[January 26]], [[1929]]). The death of Dick's twin sister had a profound effect on his writing, relationships, and every other aspect of his life, leading to the [[Motif (literature)|recurrent motif]] of the "phantom twin" in many of his books. |

||

| + | Philip K. Dick died on March 2, 1982, the result of a combination of recurrent strokes accompanied by heart failure. |

||

| − | The family moved to the [[San Francisco Bay Area]], but when Dick reached the age of five, his father was transferred to [[Reno, Nevada]]; Dorothy refused to move, so Dick's father fought for custody. Dick's mother was determined to raise Philip on her own, so she moved to [[Washington, D.C.]] where she found work. Dick was enrolled at John Eaton Elementary School from 1936 to 1938, where he completed second through fourth-grade. He was often absent from class, and he received his lowest grade (a C) in written composition, although one teacher remarked that he "shows interest and ability in story telling". In June 1938, Dorothy and Philip moved back to California. |

||

| ⚫ | After his death (he was disconnected from life support on March 2 but his EEG had been isoelectric for five days prior to that), his father Edgar brought his son's body to Fort Morgan, Colorado. When his twin Jane had died, a tombstone had been carved with both of their names on it, and an empty space for Dick's date of death. After fifty-three years, that final date was carved in, and Philip K. Dick was buried beside his sister. |

||

| − | Dick attended [[Berkeley High School (California)|Berkeley High School]] in [[Berkeley, California]] and briefly attended the [[University of California, Berkeley]], where he majored in [[German language|German]], but dropped out before completing any classes. Dick claimed to have hosted a classical music program on KSMO Radio in 1947, although details are sketchy. From 1948-1952, he worked in a record store, the only job he ever held before selling his first story in 1952. He wrote full-time, more or less, from then on. He sold his first novel in 1955. The 1950s were a hard-scrabble time for Dick, so much so that, as he once said, "we couldn't even pay the late fees on a library book." He associated with the pre-1960s [[counterculture]] of California and was sympathetic to [[beat poet]]s and the [[Communist Party]].There is some dispute regarding the latter and Dick later admitted to being literally thrown out of at least one of its rallies. Dick was opposed to the [[Vietnam War]] and he had a file at the [[Federal Bureau of Investigation|FBI]] as a result. |

||

| ⚫ | The surname ''Dowland'' is a reference to the composer John Dowland, who is featured in a number of Dick works. The title ''Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said'' is a direct reference to Dowland's best-known composition ''Flow My Teares''. Some protagonists in Dick's short-fiction bear the name Dowland. |

||

| − | In 1963, Dick won the Hugo Award for ''[[The Man in the High Castle]]''. Though hailed as a genius at this time in the SF world, the literary world as a whole was as yet unappreciative, and so he could only publish books through low-paying SF publishers such as [[ACE]]. Even in his later years, he continued to have financial troubles. In the introduction to the 1980 short story collection "The Golden Man", Dick wrote: |

||

| − | :"Several years ago, when I was ill, [[Robert A. Heinlein|Heinlein]] offered his help, anything he could do, and we had never met; he would phone me to cheer me up and see how I was doing. He wanted to buy me an electric [[typewriter]], God bless him—one of the few true gentlemen in the world. I don't agree with any of the ideas he puts forth in his writing, but that is neither here nor there. One time, when I owed the [[Internal Revenue Service|IRS]] a lot of money and couldn't raise it, Heinlein loaned the money to me. I think a great deal of him and his wife; I dedicated a book to him in appreciation. Robert Heinlein is a fine looking man, very impressive and military in stance; you can tell he has a [[military]] background, even to the haircut. He knows I'm a flipped out freak and still he helped me and my wife when we were in trouble. That is the best in humanity, there; that is who and what I love." |

||

| + | Dick's short story ''Orpheus with Clay Feet'' was one such story published under the pen name ''Jack Dowland''. |

||

| − | In 1972, Dick donated his manuscripts and papers to the Special Collections Library at [[California State University, Fullerton]] where it is archived in the Philip K. Dick Science Fiction Collection in Pollak Library. It was at Fullerton that Dick became friends with science fiction writers, [[K. W. Jeter]] and [[Tim Powers]]. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | The final novel to be published during his life was ''[[The Transmigration of Timothy Archer]]''. |

||

| − | == |

+ | ==Films and other adaptations== |

| ⚫ | A number of Dick's stories have been made into [http://www.allcinemamovies.com/movies movies], most of them only loosely based on Dick's original, using them as a starting-point for a Hollywood action-adventure story, introducing violence uncharacteristic of Dick's stories, and replacing the typically nondescript Dick protagonist with an action hero. |

||

| − | In his youth, around the age of thirteen, Dick had a recurring [[dream]] for a number of weeks. He dreamt that he was in a bookstore, trying to find an issue of ''[[Astounding Magazine]]''. This issue, when he found it, would contain a story called "The Empire Never Ended", which would reveal to him the secrets of the universe. As the dream repeated, the pile of magazines through which he was searching got smaller and smaller, but he never reached the bottom of it. Eventually, he became anxious that discovering the magazine would drive him mad (like the [[H.P. Lovecraft|Lovecraft]]ian ''[[Necronomicon]]'', promising [[insanity]] to its readers). Shortly thereafter, the dreams stopped. They never returned, but the phrase "The Empire Never Ended" would appear in his later works. |

||

| ⚫ | The most admired film adaptation is [[Ridley Scott]]'s classic movie ''[[Blade Runner]]'' (based on Dick's 1968 novel ''[[Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?]]''). Dick was apprehensive about how his story would be adapted for the film; he refused to do a novelization of the film and he was critical of it and its director, Ridley Scott, during its production. When given an opportunity to see some of the special effects sequences of [[Los Angeles]] [[2019]] , Dick was amazed that the environment was "exactly as how I'd imagined it!". Following the screening, Dick and Scott had a frank but cordial discussion of ''Blade Runner's'' themes and characters, and although they had differing views, Dick fully backed the film from then on. Dick died from a stroke less than four months before the release of the film. |

||

| − | Dick was a voracious reader of works on [[religion]], [[philosophy]], [[metaphysics]], and neo-[[Gnosticism]], and these ideas found their way into many of his stories as well as his visions. |

||

| ⚫ | Steven Spielberg's adaptation of ''[http://www.allcinemamovies.com/movie/minority-report Minority Report]'' rather faithfully translates a number of Dick's themes within an action-adventure framework, though it changes some major plot points. Similarly, ''[http://www.allcinemamovies.com/movie/total-recall Total Recall]'', based on the short story ''We Can Remember It for You Wholesale'' evokes a feeling similiar to that of the original story while streamlining the plot. It includes such Phildickian elements as the confusion of fantasy and reality, the progression towards more fantastic elements through the story, machines talking back to humans, and the protagonist's doubts about his own identity. ''Impostor'', a 2002 movie based on Dick's 1953 story of the same title, utilizes two of Dick's most common themes: mental illness, which diminishes the sufferer's ability to discriminate between reality and hallucination, and a protagonist persecuted by an oppressive government. |

||

| − | On [[February 20]], [[1974]], he was recovering from the effects of [[sodium thiopental|sodium pentothal]] administered for the extraction of an impacted [[wisdom tooth]]. Answering the door to receive a delivery of additional painkillers, he noticed the woman delivering the package was wearing a [[pendant]] with what he called the "[[vesicle pisces]]". (He probably was referring to the intersecting arcs of the [[vesica piscis]].) After her departure, Dick began experiencing strange visions. Although this may have been attributed initially to the painkillers, after weeks of these visions such a rationale becomes less probable. "I experienced an invasion of my mind by a transcendentally rational mind, as if I had been insane all my life and suddenly I had become sane," Dick told Charles Platt.<ref name=Platt/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | Throughout February and March 1974 he received a series of visions which he collectively referred to as 2-3-74, shorthand for February/March 1974. He described his initial visions as [[laser beam]]s and [[geometry|geometric]] patterns, and occasionally brief pictures of [[Jesus]] and [[ancient Rome]], which he would glimpse periodically. As the pictures increased in length and frequency, Dick claimed that he began to live a double life, one as himself and one as Thomas, a [[Christianity|Christian]] persecuted by Romans in the [[1st century]] A.D. Despite his past and continued [[drug use]], Dick accepted these visions as reality, believing that he had been contacted by a god-entity of some kind, which he referred to variously as Zebra, [[God]], and, most often, VALIS. |

||

| ⚫ | The 1995 film ''[http://www.allcinemamovies.com/movie/screamers Screamers]'' was based on a Dick short story ''Second Variety''; however, the location was altered from a war-devastated Earth in the story, to a generic science fiction environment of a distant planet in the film. ''Second Variety'' has been cited as a possible influence on the scenes in the machine-dominated future of ''The Terminator'' and its sequels. |

||

| − | ===Psychology=== |

||

| − | As time went on, he became increasingly [[paranoia|paranoid]], imagining plots against him perpetrated by the [[KGB]] or [[FBI]], who he believed were constantly laying traps for him. At one point he alleged that they had been responsible for a burglary at his house in which various documents had been stolen. However, he later stated that he had probably committed the burglary himself, and then forgotten he had done so. This is echoed especially in the character of Bob Arctor/Agent Fred in A Scanner Darkly. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | Dick himself speculated as to whether or not he may have suffered from [[schizophrenia]], and themes of mental illness permeated his work, especially that of Jack Bohlen, an "ex-schizophrenic" in the 1964 novel, ''[[Martian Time-Slip]]''. It was also prominantly featured in his novel ''[[Clans of the Alphane Moon]]'', which centered on an entire society populated from the descendants of a lunatic asylum. The topic of mental illness was of constant interest to Dick, and in 1965 he wrote an essay entitled "Schizophrenia and the Book of Changes." <ref>Sutin, Lawrence. ''Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick''. Carroll & Graf, 2005 </ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Another stage adaptation is the opera ''VALIS'', composed and with libretto by Tod Machover, which premiered at the Pompidou Center in Paris on December 1, 1987, with a French libretto. It was subsequently revised and readapted into English, and was recorded and released on CD (Bridge Records BCD9007) in 1988. |

||

| − | ===Aliases=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The surname ''Dowland'' is a reference to the composer |

||

| ⚫ | * Dick's former wife Tessa was asked in an interview why she thought his original titles have rarely been used in film adaptations (''Blade Runner'' versus ''Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?'', etc). She replied, "Actually, the books rarely carry Phil's original titles, as the editors usually wrote new titles after reading his manuscripts. Phil often commented that he couldn't write good titles. If he could, he would have been an advertising writer instead of a novelist." [http://www.farsector.com/hot_content1.htm] |

||

| + | * Dick and Ursula K. Le Guin—perhaps his only peer in terms of academic and literary reputation among late 20th-century science fiction authors—were members of the same high school graduating class (Berkeley (Ca.) High School, 1947), yet did not know one another. Le Guin (then Ursula Kroeber) had been accelerated a grade, while Dick missed much of his senior year with the agoraphobia that would plague him as an adult. Le Guin later became one of Dick's great champions (calling him "our own home-grown Borges") and wrote ''The Lathe of Heaven'' as a conscious Dick homage; the two maintained a friendship and correspondence until Dick's death. |

||

| − | Dick's short story ''Orpheus with Clay Feet'' was one such story published under the pen name ''Jack Dowland''. The protagonist desires to be the muse for a fictional author, ''Jack Dowland'', considered to be the greatest science-fiction author of the 20th century. In the story, Dowland publishes a story of his own, also entitled ''Orpheus with Clay Feet'', under the pen-name ''Philip K. Dick''. |

||

| − | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | |||

| − | Although he never used it himself, fans and critics of Dick's work often refer to him by the initialism "PKD". |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Marriages and children=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | *May 1948, to Jeanette Marlin (lasted six months) |

||

| − | *June 1950, to Kleo Apostolides (divorced 1958) |

||

| − | *1958, to Anne Williams Rubinstein (child: Laura Archer, born [[February 26]], [[1960]]) (divorced 1964) |

||

| − | *1966 or 1967 (sources conflict), to Nancy Hackett (child: Isolde, usually called "Isa") (divorced 1970) |

||

| − | *[[April 18]], [[1973]], to Tessa Busby (child: Christopher) (divorced 1976) |

||

| − | <!-- Can anyone get real, authoritative marriage/divorce dates? I get a variety of conflicting reports here --> |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Death=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| − | |||

| − | ==Works== |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===The Man in the High Castle=== |

||

| − | ''The Man in the High Castle'' ([[1962]]) takes place in an alternate [[United States]] ruled by the victorious [[Axis powers]]. It is considered a defining novel in the sub genre of [[alternate history (fiction)|alternate history]] and is the only Dick novel to win a [[Hugo Award]]. Along with ''Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?'' and ''Ubik,'' it’s one of the recommended novels to newcomers to Dick’s work at philipkdickfans.com [http://www.philipkdickfans.com/overview.htm] |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?=== |

||

| − | ''Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?'' ([[1968]]) is about the moral crisis experienced by a [[bounty hunter]] of escaped [[android]]s. It is well known as the inspiration for the influential [[1982]] film ''[[Blade Runner]].'' It constitutes both a conflation and intensification of Dick's pivotal question of what is reality and what is fake: Are the human-looking and acting androids fakes or real humans? Should we treat them as machines or humans? This is the dilemma the bounty hunter has to come to terms with. |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Ubik=== |

||

| − | ''Ubik'' ([[1969]]) uses extensive networks of psychics and a suspended state after death to create an eroding state of reality. In [[2005]], ''[[Time Magazine]]'' named it one of the hundred best [[English language]] novels published since [[1923]] [http://www.time.com/time/2005/100books/0,24459,ubik,00.html]. |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said=== |

||

| − | |||

| − | ''Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said'' ([[1974]]) is about a [[television]] star in a future [[police state]] who awakes one morning to discover that he is not famous and does not even have the identification cards crucial to his survival. Although it is not now regarded as one of his very best books, it was his first published novel after several years of silence, during which time his critical reputation had begun to grow, and was awarded the [[Campbell award (best novel)|John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel]] and is the only Dick novel nominated for both a Hugo and a [[Nebula Award]]. |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===A Scanner Darkly=== |

||

| − | ''A Scanner Darkly'' ([[1977]]) is a bleak mixture of science fiction and [[police procedural]], in which an undercover narcotics detective ingests massive amounts of a dangerous drug in order to maintain his cover. It was adapted into [[A Scanner Darkly (film)|an upcoming film]] by [[Richard Linklater]] which opens on [[July 7]], [[2006]]. It is currently the best-selling Dick book on [[Amazon.com]] [http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/search-handle-url/002-5943982-9389629?page=1&url=ix%3Dbooks%26rank%3D%252Bpmrank%26fqp%3Dauthor%2501Dick%252C%2520Philip%2520K.%26nsp%3Dscore%2501proj-unit-sales%2502bin-fields%2501none%26sz%3D10%26pg%3D1&fpn=1&rank=%2Bsalesrank&x=16&y=7]. |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===VALIS=== |

||

| − | |||

| − | ''VALIS,'' ([[1980]]) is perhaps Dick’s most [[postmodern]] and [[autobiographical novel]], examining his own supposed encounters with a divine presence. It may also be considered the most academically studied work and was adapted into an [[opera]] by [[Tod Machover]] [http://web.media.mit.edu/~tod/Tod/valiscd.html]. It was voted Dick‘s best novel at philipkdickfans.com [http://www.philipkdickfans.com/pkdweb/HorseraceResults.htm] |

||

| − | |||

| − | His later works, especially the [[VALIS trilogy]], were heavily [[autobiography|autobiographical]], many with 2-3-74 references or influences. [[VALIS]] is an acronym for ''Vast Active Living Intelligence System''; he used this term as the title of one of his novels (and continued the theme in at least three more books) and later theorized that VALIS was both a "reality generator" and a means of extraterrestrial communication. At one point, Dick claimed to be in a state of [[enthousiasmos]] with VALIS, where he was informed his infant son was in danger. Another event was an episode of [[xenoglossia]], when Dick's wife discovered him speaking [[Koine Greek]], an ancient dialect used to write the [[New Testament]] and the [[Septuagint]]. A decade earlier, Dick claimed he was able to think, speak, and read fluent [[Latin]] under the influence of [[Sandoz Laboratories|Sandoz]] [[LSD-25]]. In his essay, ''Will the [[Atomic Bomb]] Ever be Perfected, And if so, What becomes of [[Robert A. Heinlein|Robert Heinlein]]?'', Dick mentions that he began seeing pink light during an LSD experience, eight years before he wrote and attributed the so-called pink lasers to VALIS. |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===Exegesis=== |

||

| − | Regardless of the feeling that he was somehow experiencing a divine communication, Dick was unable ever to fully rationalize the events. For the rest of his life, he struggled to fully comprehend what was occurring, questioning his own sanity and perception of reality. He transcribed what thoughts he could into an 8,000 page, million word [[journal]] dubbed the ''[[Exegesis (book)|Exegesis]]''. |

||

| − | |||

| − | He spent sleepless nights furiously writing into this journal, in some instances high on large quantities of [[amphetamine]]s, which no doubt contributed to its eclectic tone. A recurring theme in the ''Exegesis'' is Dick's hypothesis that [[history]] had been stopped in the 1st century, and that "The [Roman] Empire never ended". He saw [[Rome]] as the pinnacle of [[materialism]], which, after forcing the [[Gnostics]] underground 1900 years earlier, had kept the population of the Earth as slaves to worldly possessions. Dick believed that VALIS had contacted him and unnamed others to induce the "[[impeach]]ment" of [[Richard M. Nixon]], whom Dick believed to be the current Emperor incarnate. |

||

| − | |||

| − | ==Influence and legacy== |

||

===Awards=== |

===Awards=== |

||

| + | *[[wikipedia:Hugo Awards]] |

||

| − | During his lifetime, Dick was awarded with: |

||

| − | *[[Hugo Award]]s |

||

**Best Novel |

**Best Novel |

||

| − | ***1963 - '' |

+ | ***1963 - ''The Man in the High Castle'' (winner) |

| − | ***1975 - '' |

+ | ***1975 - ''Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said'' (nominee) |

**Best Novelette |

**Best Novelette |

||

| − | ***1968 - '' |

+ | ***1968 - ''Faith of Our Fathers'' (nominee) |

| − | * |

+ | *Nebula Awards |

**Best Novel |

**Best Novel |

||

| − | ***1965 - '' |

+ | ***1965 - ''Dr. Bloodmoney'' (nominee) |

| − | ***1965 - '' |

+ | ***1965 - ''The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch'' (nominee) |

***1968 - ''[[Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?]]'' (nominee) |

***1968 - ''[[Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?]]'' (nominee) |

||

| − | ***1974 - '' |

+ | ***1974 - ''Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said'' (nominee) |

| − | ***1982 - '' |

+ | ***1982 - ''The Transmigration of Timothy Archer'' (nominee) |

| − | * |

+ | *John W. Campbell Memorial Award |

** Best Novel |

** Best Novel |

||

| − | ***1975 - '' |

+ | ***1975 - ''Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said'' (winner) |

| + | ==Biographies== |

||

| − | ===Films and other adaptations=== |

||

| + | * Carrère, Emmanuel. Bent, Timothy. (translator) (2005). ''I Am Alive and You Are Dead: A Journey into the Mind of Philip K. Dick''. Picador. ISBN 0312424515 |

||

| ⚫ | A number of Dick's stories have been made into [ |

||

| + | * Dick, Ann R. (Former Wife). (1995). ''Search for Philip K. Dick, 1928-1982: A Memoir and Biography of the Science Fiction Writer''. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0773491376 |

||

| + | * Mason, Daryl. (2006). ''The Biography of Philip K. Dick''. Gollancz. ISBN 0575072806 |

||

| + | * Rickman, Gregg. (1989). ''To the High Castle: Philip K. Dick: A Life 1928-1962''. Fragments West. |

||

| + | * Sutin, Lawrence (Official biographer). (1989). ''Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick''. Citadel Press; Rep edition. ISBN 0806512288 |

||

| + | * Williams, Paul. (1986). ''Only Apparently Real - The Worlds of Philip K. Dick''. Entwhistle Books. ISBN 0934558310 |

||

| + | ==Interviews== |

||

| ⚫ | The most admired film adaptation is [[Ridley Scott]]'s classic movie ''[[Blade Runner]]'' (based on Dick's 1968 novel ''[[Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?]]''). Dick was apprehensive about how his story would be adapted for the film; he refused to do a novelization of the film and he was critical of it and its director, Ridley Scott, during its production. When given an opportunity to see some of the special effects sequences of Los Angeles 2019, Dick was amazed that the environment was "exactly as how I'd imagined it!". Following the screening, Dick and Scott had a frank but cordial discussion of ''Blade Runner's'' themes and characters, and although they had differing views, Dick fully backed the film from then on. |

||

| + | * Apel, D. Scott. (1999). ''Philip K. Dick : The Dream Connection''. The Impermanent Press. ISBN 1886404038 |

||

| + | * Lee, Gwen (ed). ''What If Our World Is Their Heaven? The Final Conversations Of Philip K. Dick''. Overlook Press. ISBN 1585673781 |

||

| + | * Rickman, Gregg. (1984). ''Philip K. Dick: In His Own Words''. Fragments West. |

||

| + | * Rickman, Gregg. (1985). ''Philip K. Dick: The Last Testament''. Fragments West. |

||

| + | ==External links== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | *[[wikipedia:Philip K. Dick|Wikipedia article on Philip K. Dick]] |

||

| − | |||

| + | *[http://www.philipkdick.com/ Official website] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | *[http://www.popsubculture.com/pop/bio_project/philip_k_dick.html Philip K Dick Biography] - PopSubCulture.com - with additional essays and analysis |

||

| − | |||

| + | *[http://www.philipkdickfans.com/main.htm Philip K. Dick fans (with many articles & interviews)] |

||

| ⚫ | The film ''[ |

||

| + | *[http://www.pkdickbooks.com/ The Philip K. Dick Bookshelf] - A complete pictorial bibliography of Philip K Dick with more than 1200 coverscans |

||

| − | |||

| + | *[http://www.yetanotherbookreview.com/selected_stories_of_philip_k.htm Review of PKD's Selected Stories] |

||

| − | The French film ''[[Barjo]]'' ("Confessions d'un Barjo") is based on Dick's non-sf book ''[[Confessions of a Crap Artist]]''. |

||

| + | *[http://downlode.org/etext/pkdicktionary.html The PKDicktionary], originally authored by Simon Hickinbotham |

||

| − | |||

| + | *[http://web.tiscali.it/ausonia/saggistica/bibliografia_pkd.html VALBS]: Vast, Active, Living Bibliographic System: Dick's secondary bibliography online |

||

| − | The animated film ''[[A Scanner Darkly (movie)|A Scanner Darkly]]'' (based on [[A Scanner Darkly|Dick's novel by that name]]) is scheduled for release in July 2006, and will star Keanu Reeves as Fred/Bob Arctor and Winona Ryder as Donna. Robert Downey Jr. and Woody Harrelson, actors both noted for drug issues, are also cast in the film. The film was produced using the process of [[rotoscoping]]: it was first shot in live-action then the live footage was animated over. |

||

| + | *[http://dmoz.org/Arts/Literature/Authors/D/Dick,_Philip_K./ Open Directory entry for Philip K. Dick] |

||

| − | |||

| + | *[http://www.philipkdickfans.com/weirdo.htm Robert Crumb comic strip about Philip K. Dick's theophany] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | *[http://web.archive.org/20021205235217/www.geocities.com/pkdlw/index.html A fan's website with an extensive bibliography and many photos] |

||

| − | |||

| + | *[http://www.pkdandroid.com/ Philip K. Dick Comes to Life in Robotic Form] |

||

| − | At least one of Dick's works has been adapted for the legitimate stage: ''[[Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said]]'', was presented by the New York-based avante-garde company [[Mabou Mines]] in 1988 and has subsequently been produced elsewhere. |

||

| + | *[http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/11.12/philip_pr.html ''The Second Coming of Philip K. Dick''] by Frank Rose, an article from ''Wired Magazine'' about movies based on the Dick's novels |

||

| − | |||

| + | *[http://web.archive.org/20040621084106/www.geocities.com/pkdlw/howtobuild.html How To Build A Universe That Doesn't Fall Apart Two Days Later] (Essay by PKD on his "discovery" that we are living in the Roman Empire) |

||

| ⚫ | Another stage adaptation is the |

||

| + | *[http://www.ocweekly.com/ink/02/43/cover-ziegler.php A Very PhilDickian Existence] |

||

| − | |||

| + | *[http://www.timboucher.com/journal/2005/03/secret-gray-robed-christians.html The Secret Gray-Robed Christians] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | *[http://www.toeradio.org/archives/2004/10/program_10.html Benjamen Walker talks with authors Jonathan Lethem and Josh Glenn about the Science Fiction genius Philip K Dick in his podcast.] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| + | *[http://www.nndb.com/people/502/000022436/ NNDB entry for Philip K. Dick] |

||

| + | *[http://www.phildickiangnosticism.com Examination of Gnostic themes in Dick's life] |

||

| + | *[http://del.icio.us/0bvious/philip-k-dick Various articles on Philip K. Dick's ideas and fiction] |

||

| + | *[http://del.icio.us/hugeentity/philip-k-dick Various Philip K. Dick related links] |

||

| + | {{Wikipedia}} |

||

| + | [[ja:フィリップ・K・ディック]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Authors|Dick, Philip K.]] |

||

| + | [[Category:Real-world articles]] |

||

Revision as of 03:15, 8 January 2020

Philip Kindred Dick (b. December 16, 1928 Chicago, Illinois d. March 2, 1982, Santa Ana, California) , often known by his initials PKD, was an American science fiction writer and author of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the basis for the 1982 film Blade Runner.

In addition to thirty-eight books currently in print, Dick produced a number of short stories and minor works which were published in pulp magazines. At least seven of his stories have been adapted into films. Though hailed during his lifetime by peers such as Stanisław Lem, Robert A. Heinlein and Robert Silverberg, Dick received little general recognition until after his death.

Foreshadowing the cyberpunk sub-genre, Dick brought the anomic world of California to many of his works, drawing upon his own life experiences in novels like A Scanner Darkly. His novels and stories frequently used plot devices such as alternate universes and simulacra, worlds inhabited by common working people, rather than galactic elites. "There are no heroics in Dick's books," Ursula K. LeGuin wrote, "but there are heroes. One is reminded of [Charles] Dickens: what counts is the honesty, constancy, kindness and patience of ordinary people."

His acclaimed novel, The Man in the High Castle, bridged the genres of alternate history and science fiction, resulting in a Hugo Award for Best Novel in 1963. Dick chose to write about the people he loved, placing them in fictional worlds where he questioned the reality of ideas and institutions. "In my writing I even question the universe; I wonder out loud if it is real, and I wonder out loud if all of us are real," Dick wrote.

Dick's stories often descend into seemingly surreal fantasies, with characters discovering that their everyday world is an illusion, emanating either from external entities or from the vicissitudes of an unreliable narrator. "All of his work starts with the basic assumption that there cannot be one, single, objective reality," Charles Platt writes. "Everything is a matter of perception. The ground is liable to shift under your feet. A protagonist may find himself living out another person's dream, or he may enter a drug-induced state that actually makes better sense than the real world, or he may cross into a different universe completely." These characteristic themes and the atmosphere of paranoia they generate are sometimes described as "Dickian" or "Phildickian."

Dick occasionally wrote using pen names, most notably Richard Philips and Jack Dowland.

He married five times, and had two daughters and a son. All five marriages ended in divorce.

Philip K. Dick died on March 2, 1982, the result of a combination of recurrent strokes accompanied by heart failure.

After his death (he was disconnected from life support on March 2 but his EEG had been isoelectric for five days prior to that), his father Edgar brought his son's body to Fort Morgan, Colorado. When his twin Jane had died, a tombstone had been carved with both of their names on it, and an empty space for Dick's date of death. After fifty-three years, that final date was carved in, and Philip K. Dick was buried beside his sister.

The surname Dowland is a reference to the composer John Dowland, who is featured in a number of Dick works. The title Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said is a direct reference to Dowland's best-known composition Flow My Teares. Some protagonists in Dick's short-fiction bear the name Dowland.

Dick's short story Orpheus with Clay Feet was one such story published under the pen name Jack Dowland.

In the semi-autobiographical novel Valis, the protagonist is called Horselover Fat. Philip, or Phil-Hippos is Greek for Horselover, Dick is German for Fat.

Films and other adaptations

A number of Dick's stories have been made into movies, most of them only loosely based on Dick's original, using them as a starting-point for a Hollywood action-adventure story, introducing violence uncharacteristic of Dick's stories, and replacing the typically nondescript Dick protagonist with an action hero.

The most admired film adaptation is Ridley Scott's classic movie Blade Runner (based on Dick's 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?). Dick was apprehensive about how his story would be adapted for the film; he refused to do a novelization of the film and he was critical of it and its director, Ridley Scott, during its production. When given an opportunity to see some of the special effects sequences of Los Angeles 2019 , Dick was amazed that the environment was "exactly as how I'd imagined it!". Following the screening, Dick and Scott had a frank but cordial discussion of Blade Runner's themes and characters, and although they had differing views, Dick fully backed the film from then on. Dick died from a stroke less than four months before the release of the film.

Steven Spielberg's adaptation of Minority Report rather faithfully translates a number of Dick's themes within an action-adventure framework, though it changes some major plot points. Similarly, Total Recall, based on the short story We Can Remember It for You Wholesale evokes a feeling similiar to that of the original story while streamlining the plot. It includes such Phildickian elements as the confusion of fantasy and reality, the progression towards more fantastic elements through the story, machines talking back to humans, and the protagonist's doubts about his own identity. Impostor, a 2002 movie based on Dick's 1953 story of the same title, utilizes two of Dick's most common themes: mental illness, which diminishes the sufferer's ability to discriminate between reality and hallucination, and a protagonist persecuted by an oppressive government.

John Woo's 2003 film, Paycheck, was a very loose adaptation of Dick's short story of that name, and suffered greatly both at the hands of critics and at the box office.

The 1995 film Screamers was based on a Dick short story Second Variety; however, the location was altered from a war-devastated Earth in the story, to a generic science fiction environment of a distant planet in the film. Second Variety has been cited as a possible influence on the scenes in the machine-dominated future of The Terminator and its sequels.

Dick himself wrote a screenplay for an intended film adaptation of Ubik in 1974, but the film was never made.

Another stage adaptation is the opera VALIS, composed and with libretto by Tod Machover, which premiered at the Pompidou Center in Paris on December 1, 1987, with a French libretto. It was subsequently revised and readapted into English, and was recorded and released on CD (Bridge Records BCD9007) in 1988.

Trivia

- Dick's former wife Tessa was asked in an interview why she thought his original titles have rarely been used in film adaptations (Blade Runner versus Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, etc). She replied, "Actually, the books rarely carry Phil's original titles, as the editors usually wrote new titles after reading his manuscripts. Phil often commented that he couldn't write good titles. If he could, he would have been an advertising writer instead of a novelist." [1]

- Dick and Ursula K. Le Guin—perhaps his only peer in terms of academic and literary reputation among late 20th-century science fiction authors—were members of the same high school graduating class (Berkeley (Ca.) High School, 1947), yet did not know one another. Le Guin (then Ursula Kroeber) had been accelerated a grade, while Dick missed much of his senior year with the agoraphobia that would plague him as an adult. Le Guin later became one of Dick's great champions (calling him "our own home-grown Borges") and wrote The Lathe of Heaven as a conscious Dick homage; the two maintained a friendship and correspondence until Dick's death.

Awards

- wikipedia:Hugo Awards

- Best Novel

- 1963 - The Man in the High Castle (winner)

- 1975 - Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said (nominee)

- Best Novelette

- 1968 - Faith of Our Fathers (nominee)

- Best Novel

- Nebula Awards

- Best Novel

- 1965 - Dr. Bloodmoney (nominee)

- 1965 - The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (nominee)

- 1968 - Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (nominee)

- 1974 - Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said (nominee)

- 1982 - The Transmigration of Timothy Archer (nominee)

- Best Novel

- John W. Campbell Memorial Award

- Best Novel

- 1975 - Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said (winner)

- Best Novel

Biographies

- Carrère, Emmanuel. Bent, Timothy. (translator) (2005). I Am Alive and You Are Dead: A Journey into the Mind of Philip K. Dick. Picador. ISBN 0312424515

- Dick, Ann R. (Former Wife). (1995). Search for Philip K. Dick, 1928-1982: A Memoir and Biography of the Science Fiction Writer. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0773491376

- Mason, Daryl. (2006). The Biography of Philip K. Dick. Gollancz. ISBN 0575072806

- Rickman, Gregg. (1989). To the High Castle: Philip K. Dick: A Life 1928-1962. Fragments West.

- Sutin, Lawrence (Official biographer). (1989). Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick. Citadel Press; Rep edition. ISBN 0806512288

- Williams, Paul. (1986). Only Apparently Real - The Worlds of Philip K. Dick. Entwhistle Books. ISBN 0934558310

Interviews

- Apel, D. Scott. (1999). Philip K. Dick : The Dream Connection. The Impermanent Press. ISBN 1886404038

- Lee, Gwen (ed). What If Our World Is Their Heaven? The Final Conversations Of Philip K. Dick. Overlook Press. ISBN 1585673781

- Rickman, Gregg. (1984). Philip K. Dick: In His Own Words. Fragments West.

- Rickman, Gregg. (1985). Philip K. Dick: The Last Testament. Fragments West.

External links

- Wikipedia article on Philip K. Dick

- Official website

- Philip K Dick Biography - PopSubCulture.com - with additional essays and analysis

- Philip K. Dick fans (with many articles & interviews)

- The Philip K. Dick Bookshelf - A complete pictorial bibliography of Philip K Dick with more than 1200 coverscans

- Review of PKD's Selected Stories

- The PKDicktionary, originally authored by Simon Hickinbotham

- VALBS: Vast, Active, Living Bibliographic System: Dick's secondary bibliography online

- Open Directory entry for Philip K. Dick

- Robert Crumb comic strip about Philip K. Dick's theophany

- A fan's website with an extensive bibliography and many photos

- Philip K. Dick Comes to Life in Robotic Form

- The Second Coming of Philip K. Dick by Frank Rose, an article from Wired Magazine about movies based on the Dick's novels

- How To Build A Universe That Doesn't Fall Apart Two Days Later (Essay by PKD on his "discovery" that we are living in the Roman Empire)

- A Very PhilDickian Existence

- The Secret Gray-Robed Christians

- Benjamen Walker talks with authors Jonathan Lethem and Josh Glenn about the Science Fiction genius Philip K Dick in his podcast.

- NNDB entry for Philip K. Dick

- Examination of Gnostic themes in Dick's life

- Various articles on Philip K. Dick's ideas and fiction

- Various Philip K. Dick related links

| This page uses content from the English Wikipedia. The original content was at Philip K. Dick. The list of authors can be seen in the page history. As with the Off-world: The Blade Runner Wiki, the content of Wikipedia is available under the GNU Free Documentation License. |